10) The Internet

So, as the Millennium turned, what was your relationship to Shadowland?

I didn’t have one.

Were you still getting Frances Farmer mail?

The letters and phone calls, and increasingly email, on that subject remained fairly steady in the six years after Cobain’s death.

But you didn’t respond to any of it.

I just ignored it.

Let’s talk about the advent of the internet in the late ’90s for a moment. Did it significantly change your life as a film critic?

Tremendously, both positively and negatively.

What was the positive?

The positive was, of course, the growing instant accessibility it gave to a galaxy of information that had previously been unattainable, or nearly so. Also, it opened me up to a vast new audience. My stuff had long been syndicated by the Hearst and New York Times News Service but it was now available to anyone in the world at the click of a key. Since I often tended to take a minority position on a film, I seemed to be on Rotten Tomatoes every week after that site was launched in 1998.

What was the negative?

The negative was that it also opened me up to a world of instant feedback that was usually negative and often abusive. Before the internet, when people got angry at you because you panned a film they liked, and wanted to vent on you, they would have to go to the trouble to write a letter, look up your address, pay for a stamp, and walk the envelope to a mail box. Somewhere in that process, most angry readers tended to cool off and abandon the task. But in the Age of the Internet, the process of complaint became instantaneous.

It upped your hate mail.

Exponentially, and because it was so immediate and so anonymous, it seemed to give a venue to the absolute worst in people. The tone of so many of these emails I was getting was really ugly and intolerant and threatening, especially after a negative review of the latest comic-book movie. It was, “You’re fucking scum and you should die!” Really terrible stuff. Of course, I’m not the only one who got this. It was more than half the mail of every movie critic and most other journalists I knew. On one level you could laugh it off but there was so much of it that it was unsettling. There was a mob out there, and it wanted to lynch you.

Weren’t you a target in a famous internet harassment case? I remember reading about it in the Seattle Weekly.

That was later in the new decade. It involved a crazed internet vigilante who went after the film critics of the New York Times and the Washington Post and me. So I was in good company. He claimed to have gone back and studied hundreds of our reviews over the years and determined that the summaries of the plotlines in them were so inaccurate that we hadn’t really seen the movies at all. It was a conspiracy of movie critics. He carried his campaign to expose us to enormous and libelous lengths, in hundreds of emails to what must have been every newspaper and internet forum in America with a body of evidence that was pure fantasy. The New York Times, I’m told, finally took some legal action against him and he stopped.

Did you ever determine why he had a particular grudge against you?

I did. I searched back and found that, a year or two before, this guy had written me an extravagant fan email. I thanked him and he wrote me back with some of his philosophy about the movies. I answered him again and he wrote me again with an even longer email and, of course, finally, I had to end it because I didn’t need a pen pal. When I didn’t respond to his next two emails he got angry but continued writing emails that were progressively more insulting until I stopped opening them. He must have had similar experiences with those other two critics. This guy actually got it in his head that the three of us were faking reviews of movies we hadn't seen, as if that would somehow be easier than just seeing the movie and giving an opinion. It was a hint of the kind of madness the internet would later routinely give expression on a much larger scale.

If at all, how did the advent of the internet in this period affect your assessment of Shadowland?

It made it, to my mind, even more distant to anything currently going on in the world. It was a book about a guy fumbling in the darkness and paranoia of the 1970s; and now that darkness was, to a certain extent, being illuminated by a whole universe of instantly accessible information. It revealed even more mistakes I had made.

Such as?

Things as basic as the order of her films. I had Among the Living in the wrong year entirely.

Were any of these internet-revealed mistakes large enough to impact the veracity of the book?

No, but they sure made it look sloppy. It made me further discount it and see it as a slightly embarrassing antique, an irrelevant remnant of the past.

Were you aware that a number of Frances Farmer websites were launched in this period?

Only vaguely. From time to time, people would send me a link or call them to my attention. I never went to them.

When did you get the first indication that Shadowland was becoming the target of some of these sites?

I was at a press screening and a colleague came up to me just as the movie was starting and said, “Have you seen what they’re saying about you on the internet?!” I said, “No, what?” He said, “They’re saying you admitted, under oath, that you made up Shadowland, that the book is a fraud.”

Did you quiz him about this?

No, I shrugged it off. I thought: well, there’s the internet for you. But later that day, after it preyed on me for a while, I did a search and found what he was talking about. Some internet vigilante had gone through the transcript of the trial and cheery-picked statements from my testimony out of their context to make this claim.

Given the lengths your side went to prove the book was a work of your imagination, had you ever feared a misunderstanding like this might ensue?

I can’t say that I ever did.

Didn’t you think you ought to respond to it?

No, because, first, I didn’t know how to respond. How do you respond to an anonymous post on the internet? Second, the guy’s basic charge that I fabricated all the facts of Frances Farmer’s life was too ridiculous to even bother to refute. And third, and most compelling, I really didn’t care. My feeling was, let him discredit the book. It was okay by me. Maybe he was even doing me a favor.

What was the next indication that something was fundamentally changing in the public perception of the book.

An exhibitor friend named Dennis Nyback called me one day to point out that I had been seriously dissed in the pages of the Internet Movie Data Base. He was mounting a revival of Exclusive at his theater and when he looked up the movie on the IMBD, he found a long post in which the anonymous writer, calling attention to the irony that one of the actors in the movie’s 1937 cast is named “William Arnold” (my name), went on to say that Arnold’s book Shadowland was totally fiction, completely made up. Dennis was angry and thought I should confront IMDB on it at once.

And I’m betting you didn’t.

No I didn’t. Honestly, I just didn’t want to get involved in this again. Let anyone say whatever he wanted. Also, I knew from experience how difficult it was to erase an inaccuracy from the annals of the internet, especially the IMDB.

Please explain.

Earlier that year I did an interview with Eva Marie Saint, one of my all-time favorite actresses. In preparing myself for it, I noticed on IMDB that she had been married twice, first to Gerald Mayer, nephew of Louis B. Mayer; the second time to Jeffrey Hayden (both film directors), to whom she was still married. But when I asked her about that first marriage, it turned out that not only was she never married to Gerald Mayer, she had never even met him! The only person she had ever been married to was Jeffrey Hayden. And she was proud of that half-century-plus successful marriage and understandably distressed by the misinformation. Since IMDB was based in Seattle (owned by Amazon.com) and I knew a number of its employees, I volunteered to correct it for her. It took me about a hundred phone calls and several months to get it taken off. I knew that if it was that much aggravation to correct such an uncomplicated mistake about a major star, there was not enough time left in my life to correct a complicated misconception about a minor star arising from an esoteric position I took in a lengthy trial twenty years earlier.

But, as this situation escalated, didn’t IMDB come to you and ask for your side of the controversy?

Yes, many months later. A friend of mine, a former Seattle Times journalist who went to work for IMDB early on, called me and said, “You’re being vehemently attacked by at least two groups who want your scalp. They say none of the things you say happened to Frances Farmer happened and they want this to go in the IMDB record.” I asked: “What things?” He said: “The lobotomy, for one.” I said: “The book doesn’t say the lobotomy happened. It deduces that it probably happened.” He said: “Well, they claimed you made up all the other things too.” I said: “What things?” He said he wasn’t sure.

Did you ask him who these vigilantes were?

I did, and he said he couldn’t divulge their identities. He said IMDB had to consider them “protected sources.” So these guys could make all kinds of charges against me and I had no right to know who they were or even what the charges were. All he could tell me was they were “incredibly organized and incredibly determined.” Welcome to the Age of the Internet. He said he would “continue to investigate the situation” and get back to me. But he never did, at least not about that matter. I have no idea what IMDB did about it. I never learned who my attackers were.

They never confronted you directly, even by email?

No.

The anonymous bullying cowardice in this reminds me of my own experience in the McCarthy Era.

Anonymous cowardly bullying would, of course, become a hallmark of the internet in the years to come.

What was their motive? What vision of Frances were they trying to promulgate?

I didn't know. It would take quite a while before I could figure that out.

Did you know why they were so vehemently after you?

I could only speculate. Part of it, no doubt, was a generational thing. I was, in their shining eyes, a "gatekeeper" of the old order who needed to be brought down. They were passionate Frances Farmer fans who probaby knew Shadowland better than I did, and discovered in it mistakes that the research ease of the internet made obvious, and made me look rather negligent. Likely this led them to the transcript of the trial, where they misconstrued out-of-context statements I had made as some sort of confession. I really don't think they could have possibly read the entire transcript.

Was it possible they blamed you for Kurt Cobain's death?

I suspected that they did but it was never spoken.

These people—whoever they were—were trying to create a scandal, yes? They were also anonymously lobbying other media with their denunciation of Shadowland.

Yes, including the P-I.

But they had no luck.

No, because it’s not as if they had found any evidence of wrong-doing on my part. They were merely echoing—and misconstruing—information that I had given on my own initiative in a public trial. That’s not much basis for a scandal or even a journalistic “gotcha.”

Did you have a sense that a cloud was gathering around you because of this? Unspoken but perceived by those around you and maybe discussed behind your back?

I did have a sense of this. A good friend of mine named Jeff Shannon, a paraplegic since a high school accident and a fellow film critic, wrote a long appreciation of me on some website, maybe Roger Ebert’s because he frequently wrote for that. A staunch defense of my character and my writing. I cried when I read it. But, of course, I wondered: why is he writing this now? I have not recently died. Why does he feel I need to be eulogized?

Didn’t Rex Reed also write a defense of you about this time?

I’m told he did. In GQ, I believe. I didn’t see it but people have told me about it. He praised the book and said something to the effect that I was the only living person who had spoken to all the primary sources of the Frances Farmer story. Now they were all gone. I suspect he was defending me from my internet posse.

Rex Reed was a great friend of the book, wasn’t he? I recall that he even joined you, by phone, on some of the talk shows promoting it. Did you ever meet him in person?

I did, years later, when he made an appearance at the Seattle Film Festival. We had a very pleasant dinner together. And, yes, he was a great friend of the book. Probably its best friend.

You have a higher opinion of him than some people.

I do have a high opinion of him, as a human being and as a critic. In my job, I got to know all the leading movie critics of my time pretty well. Roger Ebert, Gene Siskel, Pauline Kael, Leonard Maltin, Sheila Benson. Of all these, I think Rex Reed may have been the most perceptive, and certainly the most fearless, with an absolutely infallible bullshit-detector. I also think he was the most naturally gifted writer of the bunch—even more so than Pauline Kael.

Getting back to our topic, explain for me again why you ignored those internet attacks, why you didn’t fight back.

Beyond what I’ve already told you, I was also in and out of the hospital at this time, diagnosed with a life-threatening disease and given, at most, a couple of painful years left to live—years I was not about to spend worrying about Frances Farmer.

May I inquire as to the nature of this ailment?

It was an extremely rare form of amyloidosis. In all of history, only thirty cases of it have ever been recorded and medical science still knows absolutely nothing about it. Ironically, this is the same disease that eventually killed Ed Guthman, the journalist we were speaking about earlier. It’s something that seems to particularly afflict people who have written about Frances Farmer.

Fifteen years later, you look pretty healthy to me.

For many people, including me, one of the abiding legacies of the Frances Farmer story is a healthy distrust for what doctors have to say. I declined their advice for an endless series of surgeries and followed a completely naturalistic course of treatment. At my last physical, there was no trace of amyloid anywhere in my body where it might kill me. But to get back to your question, defending Shadowland was the last thing on my mind at this time.

Were they aware that the San Jose Mercury-News ran an article around this time expressing doubts that Dr. Walter Freeman operated on Frances Farmer?

Not until several years after it ran. Its source was apparently my own out-of-context statements from the trial transcript and the second of Freeman’s two sons, who contradicted the testimony of the other brother. It’s a pity the reporter didn’t talk to me first: I could have given her some perspective on the question that she obviously didn't have.

The article says you declined comment.

I have no memory of that. And I can't imagine I would stonewall a fellow journalist, no matter how laid-up I was or how irksome the subject was to me.

This brings us to the pièce de résistance in the internet campaign against you: the document, “Shedding Light on Shadowland.” Did you ever read it?

Not until several years after it was posted. It came out at the peak of my medical crisis.

How was it brought to your attention?

A lawyer friend of mine called me and said, “You need to read this. I think it’s actionable.” This was about three years after it had appeared on the internet and he thought we could prove that it had unjustly done damage to my reputation and career in those three years.

He wanted to sue the author?

He had the idea it could be a precedent-setting internet-harrassment case. He would do it on contingency. I, of course, was not interested.

But you did read the piece?

I scanned it.

What was your reaction?

I just didn’t take it very seriously. How could I? It works up to this big conclusion that I’m a Scientologist and I wrote the book to serve L. Ron Hubbard.

It lists what the author considers more than a hundred factual errors in the book.

Yes, and some of the things he itemized were errors, things I later freely acknowledged that I got wrong. Things that were easy to look up once the internet was in place and her films became available. But the guy was wrong about many of these alleged mistakes. Or he was merely disputing my take on things that were arguable or open to interpretation. You could do that with any book.

He also claims in it, or maybe in a later addendum, that he found missing records at Steilacoom to the effect that Freeman did not operate on Frances.

A record that an operation did not take place? Really? Is there a place where they keep records of all the operations that did not take place? That must be a pretty big file. I fail to see how anything of that nature could possibly be definitive.

He also contends the conditions at Steilacoom in Frances Farmer’s time were not as bad as you depicted them.

That almost made me smile. The horrific conditions at the Western State Hospital in the late 1940s was a front-page scandal in both Seattle newspapers and the Tacoma News Tribune. The testimony of hundreds of doctors and nurses and patients attest to it. No one in the State Department of Health Services has ever denied Steilacoom was a snakepit in those days. But, like the Holocaust deniers say, it never happened.

This guy claims to have spent twenty years researching her life and has pronounced himself to be the world’s foremost Frances Farmer authority.

I’m willing to let him have that title. If he researched her life for twenty years that was seventeen years longer than I did.

But he's denoucing the book, based on no evidence, as a Scientologist conspiracy! He's framing you as a seriously evil person. Doesn't that make you the least bit angry?

It seems to have made you angry.

Nothing gets my back up like meanspirited people who claim to have a monopoly on the truth.

Well, there again, that's the internet for you. It's an arena that seems to reduce all adversarial discourse to self-righteous name-calling and transform even the best people into trolls. In a face-to-face conversation, no matter what our differences, this guy and I might recognize each other's humanity and end up getting along. God knows, we have a lot in common. But that's not about to happen in the combat zone of ithe internet.

Did you ever figure out his motivation? I mean to go to that much trouble and devote that much time to attacking someone, he must have had a very personal reason.

The only clue I can see is that he says the charge—hurled by Frances in the Kibbee tapes and confirmed by many ex-soldiers to me—that Steilacoom was “the brothel of Ft. Lewis” is maliciously false. He knows this because his father was once commander of Ft. Lewis. Or words to that effect.

You think he’s trying to exonerate his father?

Could be. But I don’t really know.

Did this guy ever directly approach or reach out to you?

Never.

Did any of these people ever do anything but sneer at you behind your back?

Only one. A young woman called me a couple of years into this and identified herself as one of my vigilantes. She seemed intelligent and reasonable and just dead set against me. We spoke for nearly two hours and it was very illuminating.

This I want to hear.

As I suspected, this whole phenomenon came out of Kurt Cobain. It was from his music and his interest in her that this young woman had come to devote herself to Frances Farmer’s memory and join, on the internet, a league of other young Frances Farmer fans around the world who had similarly become dedicated to her memory in a way that was almost religious.

Religious?

Very gradually from this conversation, I realized there was a whole new vision of Frances Farmer out there that was distinct from that of Jean Radcliffe or Edith Farmer Elliot or me. A vision that grew out of Kurt Cobain's song, "Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge on Seattle" and its climactic prediction: "She'll come back as fire, to burn all the liars, and leave a blanket of ash on the ground." This was Frances Farmer as avenging angel, a Frances Farmer who had merged with the departed soul of Kurt Cobain to become this one transcendant entity that was somehow emblematic of Generation X.

Emblematic how?

I'm not completely sure. I suspect there are no words to adequately intellectualize or explain it:. It's something you have to feel, and to do that, you need to be a member of that generation.

Okay, I can understand how this might happen, but it hardly explains these people's animosity toward you.

I was the one who calliously rejected him when he reached out to me in his time of need. That's an understandable motive for animosity. But it was even more than that. This new vision could not peacefully coexist with the lobotomy. It needed a fully intact Frances Farmer for its full metaphoric force. Denying the lobotomy became a prime tenet of this whole following, almost its clarion call. In the song, Kurt/Frances is going to "burn all the liars," and, as the instigator of the lobotomy theory, I was the chief liar that needed into go in the flames.

But that's ridiculous. Cobain loved the book. He identified with you as much as with Frances Farmer. The rock historian Gillian Gaar, in her 2006 book on Nirvana's In Utero album, states flatly that the song is "based on" Shadowland, it's a tribute to it.

That was irrelevant to this new vision.

Did these people know one of the Cobain shrinks blamed his suicide on his fear of being lomotomized?

Apparently not, and amazingly so because I know the guy voiced that opinion to a number of other people. But thank God. I can only imagine how much worse it might have been if they kad known.

What were this young woman's feelings toward you?

They were conflicted. She said she had “spent years hating me” but also realized that if I hadn’t written Shadowland, she and her generation would never even have heard of Frances Farmer. This conflict was the reason for her call. She was trying to sort it out.

How did this make you feel?

The conversation actually made me feel better. I could understand what was going on.

It must have been around this same time, 2008 I believe, that this new wave of Frances Farmer adulation climaxed in West Seattle with a day of festivities honoring its native daughter. Did you take part in any of this?

No.

But you knew about it?

I got a press release at the paper saying West Seattle was having a Frances Farmer Day. Screenings of her movies and lectures by various Frances Farmer authorities. They were also unveiling a star on the sidewalk of the main commercial street, modeled after what you see in the Walk of Fame on Hollywood Boulevard.

Didn’t it hurt your feelings that you, who had done so much to create the legend and was still a highly visible figure in the city, was so pointedly not invited to this event? Be honest.

Well, maybe a tinge. But only a tinge and I’m sure I wouldn’t have showed up if I had been invited. And in a strange way I was there.

How do you figure that?

The press release also said the day would be crowned with a gala dinner at a deluxe West Seattle restaurant which had taken its name from “an association with the Frances Farmer story. The restaurant was called Shadowland.

11. The Return

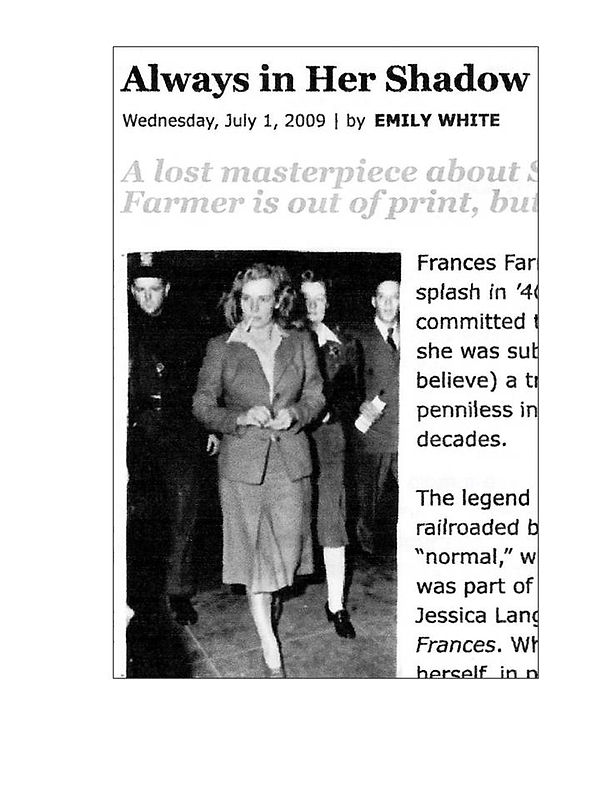

Who was Emily White and how does she enter into the story?

Emily White was a dynamic young woman who, with her husband, was involved in some way I never quite knew with the early days of Sub Pop records, the Seattle label that was responsible for the rise of Kurt Cobain and the whole grunge rock phenomenon of the late ’80s and ’90s.

She was also a writer?

When I met her in 2007 she had published two successful nonfiction books on pop culture subjects. She had also written magazine journalism and fiction, and had been the editor of The Stranger, Seattle’s alternative newspaper.

How did she first come into your life?

She was hired that year to be the arts & entertainment editor of the P-I. This was the year before the paper folded in the Great Recession. Even though she had no daily newspaper

experience, the powers-that-be felt she had her finger on the pulse of the times and might be able to lure in younger readers. One of those desperate acts many newspapers were trying in those last hours as the bell was tolling.

She was your boss?

Technically yes, and it was a stormy reign for her. Heading up a department of critics who were all over fifty and had all been on the job for more than twenty years, urging them to pander to the concerns of illiterate sixteen-year-olds. It was a losing fight and she was out of there pretty fast but in her final days we became friends.

You bonded over Frances Farmer.

One day, in an A&E staff meeting, it came up that I had written Shadowland. I think we were discussing a Kurt Cobain documentary that was opening that week. She almost fell out of her chair. She really loved the book and felt it was an important one in her life and for her generation. And she couldn’t get over the strange irony of suddenly finding herself the boss of its author. Over the next few weeks, she kept engaging me in conversation about the book and its strange aftermath, and it was always in such a pleasant and flattering way that I could hardly resist. Finally, one day, she said, “I want to write a story about this.”

About the book, or you?

The way she described it, it would be about my relationship to the book in the years after it was written. She wanted me to sit for a series of interviews about it.

Which, of course, you did not want to do.

God, no. I told her, no way. I should stress here that we had become pretty good friends by this time. I really liked her. She was, in many ways, an extraordinary person. A unique and gifted writer, and an authentic rebel and maverick by nature. She was one of just two or three women I’ve met in my life who I thought could have been the reincarnation of Frances Farmer. So it was not as if we had an adversary relationship. But I told her I had absolutely no interest in being interviewed on this subject, and, of course, there was no way she could force me.

How then did she break you down?

It was ultimately my wife Kathie who did that. She thought it would be therapeutic and urged me to do it. I still didn’t want to until one day she asked me, “When was the last time you actually read Shadowland?” I thought back and realized it had been over thirty years, when it was in galleys. She said, “Why don’t you take a few days off, try to forget everything that happened after the book was published and read it as if it were for the first time. I think you’ll be surprised. If, after that, you don’t want to do the interview, I’ll stop bugging you and never say another word about it.”

So that’s what you did?

Very reluctantly.

What was your reluctance to just read it?

I was afraid of it. Afraid of the mistakes I knew were in it. Afraid of the emotions it would arouse. Afraid it would be so amateurish it would be embarrassing. All of that.

And what was your reaction?

I really liked it. In fact, I loved it. It grabbed me from the opening line and carried me right through to the end with great drive and force. I couldn’t, as they say, put it down.

Were you as surprised as your wife thought you might be?

Even more so. All those things that I had wrong that seemed so gigantic in my mind were very tiny, miniscule, in the larger flow of the thing. I also thought it was a completely honest expression. It didn’t overstate anything. It didn’t assume knowledge I did not have. The disarming simplicity of it seemed very captivating and just right for the mission it undertakes.

So what effect did this have on you?

It was almost miraculous. It was as if a huge weight had been lifted from my chest: a weight that had been growing for over three decades without me being fully aware of it.

Did you do the interviews?

Yes, and that was further illuminating, and relieving, to me. Emily had known Kurt Cobain and knew much more about his Frances Farmer fixation than had been written. She thought the conclusion of the Cobain shrink who called me after the suicide was a minority opinion, at best, among that staff of professionals and she thought the book's new strain of internet criticism off the trial transcript was just nonsense. She also believed in the Freeman lobotomy and thought her generation’s need to believe it did not happen, this new religious faith that it could not have happened, was an almost jihadist kind of denial in the face of so much evidence to the contrary.

Did she ever write the article?

She did. At the end of the interviews, some crisis made her quit the P-I in a huff and she became editor of City Arts, a Seattle arts magazine. The piece ran there and it was very perceptive and positive. I will always be grateful to Emily White. Few people in my life have ever done me such a favor.

From that point on, Frances Farmer stopped chasing you.

That’s a good way to put it. I made peace with her and whatever role I had played in her legacy.

And this epiphany led to where we are right now?

It did, though more than five years would pass before we would get here.

You said earlier that once you decided to do this reissue, you went on a campaign to re-familiarize yourself with the subject. What exactly did that involve?

I felt I needed to both reexamine all my original research material—interview notes, copies of records and everything else I had gathered thirty years ago—and read everything on the subject of Frances Farmer which had been gathered by others in those decades since.

Which was considerable.

It included the several Frances Farmer websites, a book that had been written about her life and films, and more than twenty books that dealt parenthetically with the case and offered some new commentary or information. I also gathered copies of her films, which were all now available in sanctioned or bootlegged copies. As you know, I had never seen some of them, and some I had seen were in such poor or truncated collector’s copies that it was almost like never having seen them.

So you could judge her career through the eyes of a film critic with more than thirty years’ experience?

It seemed an interesting idea.

How long was this process of reinvestigation?

It stretched out over about a year. One thing kept leading to another. Also, I had all those letters sent to me from people around the world about Frances Farmer that I had shuffled into boxes down through the decades and never read, some of which I reasoned could contain valuable information. I decided to finally read them all and that took time.

This must have been a fairly scary process for you.

It was terrifying, at least at first. I started out where I began all those years ago, by watching Come and Get It from beginning to end for the second time in my life.It took me half a day to work up the nerve to pop the disc into my DVD player. I literally had to force myself.

What about the film scared you?

I think I was afraid I might have no reaction to it. I feared that after thirty-plus years of being intimately involved with movies, that first scene of her would have no impact on me and the whole journey it sparked would seem adolescent and silly. But I’m happy to report that those images affected me almost as powerfully as they did when I was in my twenties. The magic was still there.

Did the luxury of being able to intimately view all her films provide you with any precious moments you’d care to share?

Yes, and I’ll tell you one if you’ll allow me to drop another name. Back in 1986 I was having lunch with Anthony Perkins, who was in Seattle promoting Psycho III, and he said to me: “We have a rare thing in common.” I said: “What’s that?” He said: “An intimate relationship with someone we’ve only seen on film.” In his case he was talking about his father, the actor Osgood Perkins, who died just before he was born. So I asked him: “Do you ever watch your father’s films, trying to get a sense of what he must have been like?” And he said: “Often, but I never look too close when he’s center screen because that’s when he’s acting. I always look at him closely when he’s at the side of the screen and the other actors are on. I figure that fellow is my real father.” I always remembered this and when I began my Frances Farmer film festival I tried it.

Were you able to spot the “real” Frances that way?

I believe I did. There’s this moment at the end of Rhythm on the Range, a musical she made with her fellow Washingtonian, Bing Crosby, who she adored. Crosby is singing the final number, the reprise, and most of the cast is gathered in a circle in the background. Her figure is far away, almost off camera. But if you look close, you can see that she’s joking with the actors next to her and smiling this radiantly happy smile and maybe she’s glad the whole thing is about over. Anyway, clearly, she’s not acting and I figure that’s a glimpse of the real her.

How would you define that “real” her?

The image, or I guess you would call it scene, instantly evokes the first of the two women she played in Come and Get It, the dance hall character. Howard Hawks told me that he modeled that character after her own personality. Saucy, a good sport, one of the boys but smarter than all of them put together and just blooming with wholesome beauty. The ultimate Hawksian woman. It all comes together in that off-camera moment in Rhythm on the Range in a way I found strangely heartbreaking.

Viewing her work en masse, is there anything about her as an actress that bothers you? Something you can criticize?

If I had to pick one thing it would be her voice. Don’t get me wrong, she had a uniquely terrific voice, and a voice that embodied her persona—which is the prime requirement of all true movie stars in the sound era. But she tended to affect a mid-Atlantic, Katherine Hepburn-esque, actor-ish quality to that voice which often rings false to me. No one who grew up in Seattle ever spoke like that naturally.

After your full look at her film career, how do you rate it?

I think she was definitely a major talent and she holds her own with some of the biggest stars of all time. There are plenty of moments in Toast of New York in which she knocks Cary Grant right off the screen. That spark of true cinematic sorcery—which is one of the rarest commodities on earth—distinguishes her from that vast second tier of almost-stars in the Golden Age of Hollywood. She was not so much a might-have-been as a should-have-been. Even in the relatively few films she made, she managed to create a number of mesmerizing characterizations, particularly in some of the lesser films like Among the Living and Ebb Tide. I think her later roles, Son of Fury and even The Party Crashers, show she might have developed into a substantial character lead, in the vein of the later Katharine Hepburn or Helen Mirren.

As we talked about earlier, a number of writers, scholars and lecturers have cropped up in recent years who claim to be authorities on Frances Farmer. I assume you read their work. What did you think of it?

I found much of it very interesting and eye-opening. They’ve really been able to nail down many of the details of her life with a thoroughness that was beyond me in the ’70s. The internet has been a magic wand in that respect.

But it strikes me that all of this research was several degrees of seperation from the people who actually lived the story.

Well, so was mine. I never met Frances Farmer.

But you met and became friends with Belle McKenzie, the greatest influence on her life. You looked into the eyes of the mental patients and nurses and the rapists who shared her snakepit experience. You spoke directly to people like her sister Edith and her roommate Jane Rose and her interviewer and confessor Lois Kibbee. You interviewed a hundred people in Hollywood who knew her, all now long gone. That’s an immediacy to her story that no one else will ever be able to claim.

But with that immediacy came a lack of perspective. My account was never objective, or wanted to be. The distance these writers have to her life forces them to have a much wider perspective than I had.

Is there anything in this body of writing that bothers or surprises you?

I find it strange that, apparently, in all this new wave of research, none of these experts has found and read Frances’ letters to Belle McKenzie or any of the writing she did that was in Belle McKenzie’s possession when I met with her. That’s material that would seem to be indispensable to anyone who aspired to be a biographer of Frances Farmer. Maybe it’s been lost.

Was there any part of your return to Frances Farmer that you particularly enjoyed?

I enjoyed re-reading Edith’s family memoir, My Sister Frances: A Look Back with Love. I’d read it in manuscript decades before but the version she self-published shortly after Shadowland came out was quite a bit different, and much longer, than what I’d read. Its anti-Communist hysteria is still a bit numbing and Edith is not the most trustworthy of witnesses but she’s a decent writer and the book nicely fills in a good deal of their early childhood.

Was there any part of your years of flight from Frances Farmer that, when you looked back on it, you saw as an opportunity missed?

Yes. When I wrote the book I was never able to get inside the West Seattle house that she grew up in and was also the setting for so many important moments of her later life. But sometime in the ‘90s, someone who had just bought the house, or maybe the realtor who was handling the sale, called and asked if I would like to walk through the place and take some pictures while it was still empty. At the time, I didn’t want to. Now I very much regret passing on that opportunity.

In 2007, PBS did a documentary in its American Experience series on Dr. Walter Freeman. It was called “The Lobotomist.” Did you see it?

Not when it first aired but I finally did see it a few months ago as part of this campaign. It was pretty harrowing, with footage of some of the lobotomies Freeman had taken himself that I had never seen before. I thought it was very good, though it didn’t mention Frances Farmer one way or the other.

It’s based on a 2005 biography of Freeman of the same name.

I read that too and it’s also quite good, though it concludes, a little too hastily I think, that he probably didn’t perform the surgery on Frances. The author admits this is based solely on Edith’s testimony that the family stopped it before it happened.

Did the producers of that PBS show not contact you when they were putting it together?

They did. They wanted permission to use some of the photos in the book. I told them to be my guest.

Didn’t they want to interview you?

No.

They didn’t ask you anything about Frances Farmer or the controversy over whether or not Freeman worked on her?

Nothing. They didn’t ask and I didn’t volunteer.

Did the author of the Freeman biography try to contact you?

Not that I know of.

There’s so much you could have told him.

Yes, and I would have been happy to pass along what I had if he had asked.

That seems downright negligent on his part, considering he was writing what he claimed was the definitive biography of the good doctor and she was his most famous patient.

It could be something else. I have found that once you’ve sued somebody and shown your determination by going all the way through a hugely expensive trial, journalists tend to be a little wary of you.

You obviously did a great deal of reading on the subject. Was there anything in this vast library of post-Shadowland writing about Frances Farmer that you found particularly good or inspired or insightful?

By far the best analysis of the Frances Farmer story that I read in this marathon was a chapter devoted to it in a 2003 book published by the University of Washington Press called Gay Seattle: Stories of Exile and Belonging. The author is a professor at Seattle University and its primary purpose is to probe her legacy as a gay icon. But it ends up being the most balanced and thorough and interesting examination of the whole phenomenon I’ve seen in one easily digestible place. It’s also the only account out there that’s noticed how her story “has lent itself to multiple interpretations by vastly different audiences.” That’s pretty astute.

So, where, at the end of this year-long revisitation of the Frances Farmer phenomenon did this process leave you?

It left me in virtually the same place I was in when I started to write Shadowland nearly forty years before. It turned out to be, for me, an extraordinary reaffirmation of the youthful intuition that created the book.

What do you mean by “intuition” that created it?

One of the greatest books ever written about the movies is the autobiography of Frank Capra. And in it he claims that a man’s intuition is at its peak at age twenty-six. He backs this up with a lengthy list of historical characters whose careers all grew out of an insight that came to them from the ether when they were twenty-six years old. I was twenty-six when I first saw Come and Get It at the Edgemont Theater in 1972. I think that the intuition that grabbed onto that image and sensed there was one of the great American stories behind it was correct. Everything grew out of that intuition.

12. The Mystery

To close this conversation, I’d like to go back to that moment after you read the book again for the first time in all those years. Why do you think this experience had such a liberating effect on you?

Part of it was because it was so clear to me that the book still had some relevance. It was not as dated and immaterial as I had assumed.

Yet it approaches its subject as if no one reading it has ever heard of Frances Farmer. That might have been the case in 1978 but there has since been three movies, a half-dozen plays, maybe twenty other books, a mountain of journalism and web sites galore dealing with her story.

But none of the movies have been particularly successful, either critically or commercially, and they’re now long forgotten. None of those movies, or the plays or books or journalism, has been able to define her in a satisfying way, even though they’ve tried. The thing I liked when I read

American Film Magazine

Shadowland again was that it doesn’t insist that it has defined her. It regards her as an exquisitely intriguing but unsolved historical mystery: its very title speaks to the unknowability of the human heart and the futility of the art of biography. That was the right approach. That was an approach that seems to me to still have some lasting power.

You don’t think that, in the wake of all this new research, her life is less of a mystery, less of a Shadowland?

I think these researchers think they now know everything about her, and you can read that in the iron-certainty of the internet manifesto, “Shedding Light on Shadowland.” But they’ve deluded themselves. We still don’t even know for sure what year she was born.

How can that be?

Her birth certificate says 1913 but all the studio records and early biographical accounts say 1914. So did Frances herself to Lois Kibbee. Belle McKenzie claimed the 1913 date on the birth certificate was a “typist’s error” that Frances embraced when she signed her contract with Shepard Traube in 1935 because she wasn’t quite twenty-one and legal. In the book, I skirted the issue by saying, in my first-person account, that the file I found on her in the library stated she was born on September 19, 1914, which was true to my experience. But I don’t know which is right. As far as I’m concerned, it’s a mystery.

The Wikipedia and IMDB accounts also give her a middle name, “Elena,” though yours doesn’t.

She was committed as “Mrs. F.E. Anderson,” her married name, but most of the sources I spoke to thought the “E” she sometimes used as an initial in this period was for either “Erickson,” her husband’s stage name, or “Ernest,” her father’s first name. “Elena” was the name of the character Kay Francis played in the 1934 movie, British Agent, which Frances recreated in a radio version with Errol Flynn. The Indianapolis Star claimed in a 1983 article on her that it was the missing middle name on her tombstone, and her new generation of fans often use it as a codename for her in their chatter. But it’s not on her birth certificate so it’s not her middle name.

I guess it is now.

Yeah, and if these new authorities can’t even nail down her full name or the year of her birth, it’s hard to trust anything they might say about the larger questions of her sanity and what happened to her in the halls of Steilacoom. I frankly don’t think they’ve shed much light on the Shadowland of Frances Farmer’s life at all.

As we established earlier, hers is not the only epic historical mystery that has hooked you over a long period of time. Is there any common denominator to the stories of Frances Farmer, Vincent van Gogh and Warren G. Harding that has called out to you in a special way?

There must be, though I’m not sure I can put my finger on it. I suppose you could say that all three subjects are remarkable and accomplished but seriously flawed personages with a mythic scope to their lives and a demise that defies any logic and creates a haunting and addicting mystery.

And for each of these mysteries, you’ve worked your way to a possible, even probable, solution that is both profound and absolutely mindboggling in its implications.

That’s your description, not mine, but I have no argument with it.

At the same time, you seem amazingly open to other possible scenarios in all these mysteries, even Edith’s whitewashing of her family tragedy.

I don’t, by any means, feel I “own” the truth to any of these three epic historical mysteries. And I actually enjoy examining and debating the other possibilities. I don’t feel threatened by them. I also fully acknowledge that I can be wrong about things. In Edith’s case, who knows? Maybe the Communist Party of the 1930s was a lot more stressful to the mental health of Frances Farmer than a young liberal like me was willing to credit in the 1970s.

In Shadowland, you allude to the possibility that Frances was a closeted lesbian. In the years since, much has been written about this aspect of her mystery. Has any of this influenced your thinking?

Well, of course, we have all had our consciousness raised in that department since the stone age of 1978. And Gary Atkins, in his book Gay Seattle, offers new information pertaining to Frances’ sexuality and does a brilliant job of making the case for lesbianism without insisting upon it. Still, we also know that she was actively heterosexual in most periods of her life, often obsessively so: in the Kibbee tapes she attributed her whole psychological descent in the early ’40s to being rejected by her selfish lover, Clifford Odets.

What about the—what Edith called—“lesbian pornography” that punctuates the autobiography?

There was very little of it in the Kibbee tapes. So we don’t know how much of it was supplied by Frances and how much by Jean Ratcliffe. My educated guess is that Ratcliffe supplied most of it.

There’s still this hint of androgyny in her persona. Less than in, say, Dietrich or Garbo’s, but still present.

I agree. It’s just a tinge but enough to intrigue us and suggest an openhearted bisexuality that’s a strong element of her appeal.

Would you say it’s still a mystery as to whether or not there was an actual political conspiracy to put her away?

Yes, it’s still a mystery as to, for instance, how involved the FBI was in the matter or who Judge Frater or Dr. Nicholson or Charles Stone spoke to or did in the days leading up to her commitment. But, as I’ve said many times, the way the laws were written, these people didn’t need to conspire to put her away. That’s the real horror of the story.

You make a point in the book that the story of Frances Farmer is very particularly “a Seattle story,” not a Hollywood story. Do you still feel that way?

More than ever. I also feel the story has a special relevance to today’s Seattle.

Really? How so? In the years since the book came out, Seattle has become, outside of San Francisco, probably America’s most liberal and multicultural city. The conservative forces that persecuted Frances Farmer there no longer exist.

Seattle is all about the “new.” It’s the youngest city of its size in the world and the only American city that’s had two highly successful world’s fairs, each proclaiming it as “The City of the Future.” When I wrote the book, it was the city of Boeing and it’s since become the city of Microsoft, Amazon.com and Starbucks. Its nature is to embrace what’s new, and to not only forget the past but to pretend it didn’t happen. Shadowland is the darkest episode of the darkest chapter of that past: its own Salem Witch Trial, illustrating how easy it is for the legal and medical establishment of the city to commit an atrocity out of ignorance and prejudice disguised as science. As Seattle continues to grow and continues to embody the outer reaches of the new technology, I can only think such a story will have an increasing resonance—and importance—as a parable and a cautionary tale.

You said earlier that the Freeman lobotomy is irrelevant to the fate of Frances Farmer because it was just one more step of many they used to break her in Steilacoom. But it remains the frightening centerpiece of her story, don’t you think, and is thus a very important question.

Yes, as I said before, the meeting of Frances Farmer with the most barbaric cycle of medical atrocities to ever occur on U.S. soil—and not knowing, precisely, what came of that meeting—is the topper that, added to the pile of other imponderables of her fascinating life, makes her story one of the great historical mysteries. As I looked back over how hotly this question has been debated over the past thirty years, it makes me feel vindicated that I resisted the advice of Noel Marshall and others to state it in the book as a fact. It’s infinitely more powerful as a possibility than as a certainty. That was the right way to play it.

Now that you’ve done both a reissue of Shadowland and this book-length analysis of its back and post-story, are you at all afraid that you’re just opening yourself up to a whole new wave of misunderstanding and unwanted attention?

Not really. It’s hardly a hot topic these days and I don’t expect any reaction at all. It’s just my modest effort to save the book from oblivion and set the record straight.

Do you think you’ll ever be free of Frances Farmer? Or do you even want to be?

I’ve accepted the fact that I’ll never be free of her. She will always keep popping up in my life in some strange and unexpected way. She also has a way of intruding on these other mysteries that have obsessed me in recent years. It happened again just the other day. What to hear about it in one final story?

Sure.

I was in San Francisco, at that city’s Palace Hotel, where President Warren G. Harding died five days after taking sick in Seattle in late July, 1923. I stayed at the hotel for several days, in a room right down the hall from the Presidential suite, to which I had free access. In the process of this, feeling the spirit of the Harding death scene, something kept pulling my attention to the hotel’s reception desk, which is very long, very elegant, and in its own room just off the hotel’s spectacular Garden Court lobby. It’s hard to explain but it was just eerie the way I was pulled to that reception desk. It felt so familiar in a cozy déjà vu sense. Sometimes I would go down late at night, when no one was there, and just stare at it. Then, after I returned to Seattle, as I was preparing for this talk, I was looking at the book and I saw why. The Palace Hotel was where Lee Mikesell installed Frances as a reception clerk in the mid-’50s at the beginning of her “comeback.” She had worked at that very desk.

I’m surprised you didn’t see her ghost there.

Maybe I did. In a chilling moment I recalled that on one of those nights I had gone down to the lobby well after midnight and the reception room was empty except for this one woman at the desk. I remember thinking it was odd because I never saw anyone working there that late at night. The woman was tallish, with short blond hair, maybe forty years old and attractive. Our eyes met for just a second as I passed the desk and then I continued on out of the reception room.

Did she smile at you?

You know, now that you mention it, I believe she did.